Märchenmond (translated: Magic Moon) by Wolfgang und Heike Hohlbein was one of this year's guilty pleasure reads. When I fell into the targeted age range for this novel (young adult fantasy), I took no interest in the genre, but I clearly remember one of my peers reading from the book when my class was given the task to introduce their favourite reads in a series of German lessons before the winter break. This must have been in year 5 (I was 10 years of age). Annika, if I recall the girl's name correctly, introduced us all to Hohlbein's Märchenmond, and whilst she was singing the author's praises, our German teacher proceeded to passionately deride Hohlbein and his opus in the aftermath of her presentation.

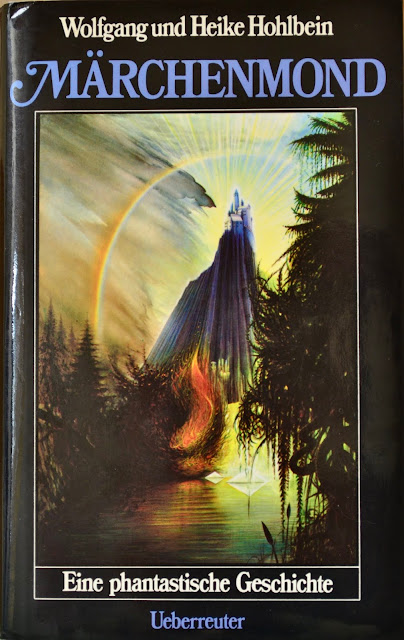

Annika's presentation did not capture my interest, whilst my German teacher's opinion on the quality of Hohlbein's work did stay in the back of my mind for years to come. Nevertheless, I was fascinated by the cover of Annika's edition (the Ueberreuter hardback, which is pictured below). The cover intrigued me and I distinctly remember coveting her hardback copy. As my mother's view of Hohlbein's output turned out to be congruent with my teacher's opinion, my pleas to buy a copy of the book just for its cover naturally failed to convince her.

Fast forward more than two decades and as part of my ongoing reading project on 1980s German fantasy literature, I finally bought my very own copy of Märchenmond. Not just because of the cover, but the cover art played a huge part in my decision to acquire the book. Of course, it had to be the Ueberreuter hardback edition with the artwork by Ernst Spalt.

|

| Wolfgang Hohlbein, Märchenmond, Ueberreuter 1st edition, cover art: Ernst Spalt |

Apart from eventually getting hold of the physical copy of this book, I also wanted to put Hohlbein to another test. Based on the sheer quantity of the author's assembly line output of fiction, Hohlbein is, solely from a commercial viewpoint, too prolific a writer and can simply not be ignored when it comes to contemporary German fantasy literature.

Having previously completed the first instalment of Hohlbein's Die Chronik der Unsterblichen in audiobook format, I wanted to give him another chance and explore at least one more book of his. As far as Chronik der Unsterblichen is concerned, I am certain that I shall not be pursuing this vampire series further. Following a promising start and an interesting premise, the story quickly descended into a seemingly never-ending, detailed and repetitive description of fight and torture scenes.

I hoped that Märchenmond, which Wolfgang Hohlbein has written together with his wife Heike and which has evidently turned many of his readers into fans of the fantasy genre, would be a different experience, perhaps one that would convince me to read other Hohlbein titles. And the big question, of course, was, whether my German teacher would be vindicated in his assessment?

Märchenmond - Very Brief Summary of the Plot

To sum up the plot, in Märchenmond we encounter Kim, a nine-year-old boy, whose younger sister, Rebecca, is not waking up from a coma following an operation. Kim later learns that his sister is held hostage by an evil magician by the name of Boraas. This interference is preventing her from regaining consciousness in the real world.

To help Rebecca, Kim himself has to embark on a journey to Magic Moon. Yet, once Kim has arrived in Magic Moon, he soon finds that his quest to free his sister is inextricably linked to saving Magic Moon from destruction by Boraas and the dark forces he has unleashed. On his perilous voyage through Magic Moon, he encounters an array of magical beings and quirky characters, including a dragon, a speaking bear and a giant, who will form a fellowship to assist him in his adventures.

So far, so good. It all sounds like a fairly standard premise for a book in the genre.

My Verdict

What becomes obvious rather quickly is that Hohlbein has attempted to produce a copy of Michael Ende's Neverending Story, and a mediocre one at that. Of course, Hohlbein has also borrowed from other writers, including Tolkien and Lewis, the similarities between Ende's novel, which was published around four years prior in 1979, and Märchenmond, which was originally published in 1983, are striking. Bluntly put, the book is a blatant attempt to ride on the waves of Ende's success.

In both novels the protagonists leave the real world to save a magic realm. Both Bastian, the young boy in Ende's Neverending Story, and Kim in Märchenmond encounter an array of characters, including a dragon and a young warrior prince, and both have to face a series of challenges before their quest is completed.

However, Ende's novel has depth and the author lovingly develops his characters, depicts his settings, engages in world building and designs a series of engaging challenges for his protagonists. In Märchenmond, on the other hand, Hohlbein simply copies the overall structure and characters of Ende's novel. However questionable this 'borrowing' of Ende's ideas may be, Hohlbein, also fails miserably in its execution, first and foremost by neglecting the development of his characters. Compared to the Neverending Story, Magic Moon remains a bland affair of haplessly assembled characters and plot elements.

What's more, the absence of world-building in Märchenmond is striking, considering that the book is after all a fantasy novel. The reader is largely left in the dark about the workings and forces that govern this world and its people, or the motivation behind Boraas's hostile takeover. Instead, Kim seems to stumble from one encounter with the dark riders into the next, leading to repetitive descriptions of fight and combat scenes, which Hohlbein, going by my experience of Chronik der Unsterblichen, seems to relish. Other types of conflict, which would allow his characters to respond and develop in meaningful ways rather than engage in close body combat, are few and far between.

Kim's initial motivation, the salvation of his sister's soul, is hardly mentioned for the best part of the second half of the book. This element of the narrative is only picked-up towards the end. By then it almost appears as an afterthought. It is also never quite explained how Rebecca is actually linked to Magic Moon and its survival. In the final chapters of the book Kim and his companions encounter an ever-expanding array of settings and characters. How these fit into the hierarchy of Magic Moon is largely left untouched as well. Perhaps Hohlbein expands on these in the sequels to the book.

The moral of the story, whilst subtly delivered through the description of Bastian's experiences and interactions in Ende's book, is, by comparison, overtly thrust into the reader's face in an utterly awkward and clumsy 'tell, don't show' style. For large parts during the final pages of the book, it appears that Hohlbein was in a hurry to make sure the audience absorbs his moral message. As he's failed to do so throughout the book, he resorts to delivering this by way of overt description and exposition in the final chapters. This comes across as awkward and amateurish; and I felt almost embarrassed reading it. I am aware that this was Hohlbein's first published novel. Yet, some passages are so riddled with platitudes, it was an utterly cringeworthy reading experience.

As far as I am aware, out of more than 200 published Hohlbein titles (some of these are ghost-written), there are merely 3 of Hohlbein's books that have been translated into English, including Märchenmond, which was published as Magic Moon by Tokyo Pop in 2006. To this day, the book remains Hohlbein's biggest success. As is evident from Märchenmond, Hohlbein borrows his plots, themes and motifs from other writers in the field, including but not limited to Michael Ende, Stephen King, H.P. Lovecraft and J.R.R. Tolkien.

Given this lack of an original contribution, to an English-speaking audience blessed with a wealth of contemporary and classic fantasy fiction, Hohlbein's output is clearly surplus to requirements and the quality of his work is surpassed by a large number of even mediocre writers in the genre.

In a German context this looks somewhat different. There he often appears to be the author of choice of many, especially younger, German readers. Considering that not many German authors were writing in the genre back in the early eighties and not forgetting the commercial success of Ende's Neverending Story, there clearly was an unquenched demand for fantasy fiction amongst the wider German readership, which accounts somewhat for Märchenmond's prolonged success and continuing popularity. With the publication of Märchenmond, Hohlbein and his publisher were able to effortlessly tap into this demand.

Yet, commercial success alone is not everything and certainly not a measure for quality. As far as Märchenmond is concerned, I wholeheartedly agree with my old German teacher. All those wishing to save themselves from a cringeworthy reading experience are well advised to give this one a miss.